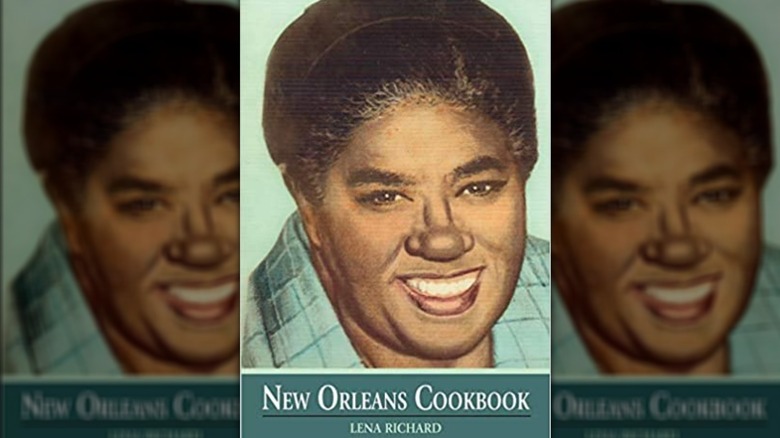

Lena Richard Was A Celebrity Chef Before Celebrity Chefs Were A Thing

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Before there was Julia, there was Lena; and we should all be talking about her a lot more.

More than a decade before Julia Child became a legend for bringing French cooking into kitchens across the country, Lena Richard hosted her own television cooking show in 1949. That feat alone is worth conversation. Add to that, Lena Richard was one of the first African Americans seen on live TV. "Not just, you know, some little 10-minute segment," New Orleans Deelightful Roux School of Cooking owner Chef Dee Lavigne said to WDSU.com about Richard's show. "She had an audience!"

Richard's audience flocked to the television twice a week to watch Richard walk through cosmopolitan New Orleans Creole recipes from her self-published cookbook. It was, according to some, the "best Creole cookbook ever written," said Smithsonian curator of African-American history, Crystal Moten, on "Sidedoor," a Smithsonian podcast.

That cookbook had put Richard's culinary skills on the map. She was recruited to be the head chef at legendary Colonial Williamsburg Travis House, a restaurant where political elites like Clementine Churchill would ask to meet Richard personally. When Richard eventually moved back home to New Orleans, she started a successful frozen-food business plus opened her own culinary school.

Oh, and she also became a television star.

If today's celebrity chef can be characterized as a culinary savant that charms an audience while teaching them the art of cooking, that archetype is an homage to Richard. Take a deeper dive into her story and you'll understand why.

The making of a culinary legend

Like many other young Black women in the Jim Crow South of the early 1900s, Richard was pigeonholed to work as a domestic. However, in a radically uncharacteristic move of the time, the woman Richard worked for recognized Richard's budding culinary talent and sent her to the celebrated Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston. There, according to Lizzie Peabody, host of the Smithsonian podcast "Sidedoor," Richard had to get written consent from every white woman in the class that they were "okay with being in class with a black woman," she said.

That was before they saw Richard's culinary talent.

Her superior skills were obvious to everyone, including Richard; and, in short order, her classmates were taking notes from her. After the course, Richard came back to New Orleans and eventually got married; started a catering business; and, in 1939, published a cookbook that would better represent Creole cuisine than the too-small view of the distinct New Orleans food culture that other cookbooks were doling out at the time.

Within the first week, Richard received hundreds of orders for her cookbook, so she decided to take it on tour to further promote it. This was the beginning of her building a nationally known name for herself; and the rest, as they say, is history.

Except, devastatingly, it isn't.

Not one Lena Richard cooking show video was saved

Despite appearing opposite iconic entertainment like "The Howdy Doody Show" on New Orleans' WDSU, what can we find in the archives of Richard's show? Nothing. Not one script was protected. Not one video remains.

According to Culinary Lore, a few years before Richard got her big television break, a woman named Dione Lucas hosted "The Dione Lucas Cooking Show." The Harvard library archives have videotapes, audiotapes, scripts, and more from her show.

What was saved from Richard's show? One still photograph from her on her set. Otherwise, nothing was saved — except people's memory of how her skilled approach of measuring and blending flavors on screen made you want to grab a paper and pencil to take notes.

A gift to the culinary integrity of New Orleans cuisine, Richard ascended to a seat at the table of other greats of her time. However, she did so while simultaneously navigating an ever-present assault on the integrity of her own personhood. From the lynching postcards that were still in distribution as she promoted her cookbook up North to the images foisted on women of color at the time, like "La Cuisine Creole," they were ever at work to either violently threaten or socially and psychologically diminish African Americans from feeling professionally qualified, experienced, or accomplished.

Luckily for us, Lena Richard was all of those things and a lot more. The heritage of a precise, multicultural New Orleans creole cuisine survives because of it.