The Rise And Fall Of TV Dinners

Pretty much everyone born during the 1950s and beyond has eaten a frozen dinner. Pop one into the lunchroom microwave and in less than five minutes you can have like three bites of mac and cheese and then spend the rest of the afternoon wishing you had something else to eat. Depending on which decade you were born in, you may or may not know that this quintessentially American convenient lunch and dinner experience has long and proud origins. Before Lean Cuisine, Healthy Choice, and Marie Callender's, there was the not-so-humble TV dinner, a bold new way of eating pseudo-food that did not require a stove top, a sink full of dishes, or a dining room table.

So bust out the TV tray, turn on some "I Love Lucy" reruns, gather the family for a less-than-wholesome meal in your living room, and enjoy this story of how the TV dinner changed the way people eat, then became an embarrassing chapter in the history of American cuisine.

It all started with a surplus of cauliflower

There's a small town legend that you should always lock your car doors in the summertime so no one will put a bag of zucchini on your front seat. If you garden, you know surplus can be a problem — you can always make tomato chutney or pasta sauce, but what can you do with 42 pounds of zucchini?

Way back in the 1940s, a guy named William Maxson had the same problem with cauliflower. This was long before cauliflower became the darling of low carb dieters, so Maxson apparently didn't know he was supposed to use the excess to make fake rice and veggie pizza crust. What to do with all that cauliflower? Well, he had some room in his freezer, so he cooked the cauliflower, stashed it, and left it to languish for a whole year until he finally remembered it existed. He took some out, tried a bite, and did not toss the whole thing into the bin in disgust. The frozen meal was born.

After that lightbulb experience, Maxson started experimenting with freezing all different kinds of food, which he would stash in his freezer and then serve to unsuspecting dinner guests. According to a 1945 profile in the New Yorker, Maxson — who was evidently a left-handed version of Henry VIII — reportedly even became a little obsessed with his idea, to the point where he hardly ever ate anything that hadn't been previously frozen.

TV dinners were originally designed to feed the military

Frozen meals may seem like an obvious fit for the overworked, unpaid American housewife of the 1940s, but that was not the first market that occurred to William Maxson. He was a Navy man, and his thoughts immediately went to all those poor sailors on Naval Air Transport who had to eat mystery rations and cold sandwiches.

Maxson designed a meal for the airborne Navy that looked remarkably similar to the ones you can pick up in the frozen section today, except somewhat more basic. These early frozen dinners were reportedly called "Sky Plates" (Get it? Because they were served in the sky?), based off Blue Plate Specials served at restaurants in decades prior. They were presented in three-compartment paper trays that included a serving of meat and two servings of vegetables. The soldiers had six options to choose from including ham steak, meatloaf stew, frankfurters with beans, and veal cutlet.

The TV dinner and the air fryer have the same origin story

Maxson was a pretty innovative guy, and he recognized that the people who were preparing and serving frozen meals onboard an aircraft would need a practical way to make them unfrozen and therefore suitable for human consumption. So Maxson sold his frozen meals alongside the "Maxson Whirlwind," a special oven he'd specifically designed to heat up six Sky Plates at a time.

The Maxson Whirlwind wasn't just a multi-level toaster oven, it was an innovative product that earned accolades from Popular Mechanics and Popular Science. It had a 120-volt DC motor and a fan that helped circulate hot air around the Sky Plates, cutting the cooking time from 30 minutes to about 15. This made the Maxson Whirlwind the world's first convection oven and Maxson himself the de facto inventor of the air fryer.

Today, we buy air fryers because they can produce crispy food that mimics deep fried favorites without all the fat, but in those days the technology was more useful as a way of decreasing cooking time and solving the "oven is always hotter on the top shelf" problem.

After WWII, commercial airlines became the primary market

At the end of World War II, there weren't as many Navy men flying around on air transport, but commercial air travel was becoming more of a thing. It wasn't a huge leap for Maxson to switch from the military market to the commercial market, and he didn't really need to change anything about his Sky Plates, either.

By 1947, Pan Am was trying out Sky Plates on a few select flights, and the future was looking bright for Maxson and his frozen meal empire. Smithsonian says he was even planning to market his frozen meals to home cooks (as "Strato-Meals," because they were born in the stratosphere or something), but he died before he had a chance to make that part of his frozen dreams come true. Really, though, it was probably a kindness that he didn't live to see Swanson take credit for an idea that very clearly belonged to him.

Bars and taverns caught on to the idea before grocery stores did

Funny thing about great ideas, they don't exist in a vacuum. Unless you keep your idea a secret — and then what good is having an idea — someone out there is going to see dollar signs and try to steal it from you. Fortunately for Maxson, none of that really happened until after he was gone, but it did happen.

Shortly after Maxson's death, an entrepreneur named Jack Fisher invented the "Fridgi-Dinner," which was pretty much the same thing as a Sky Plate except it wasn't airborne and the people who ate it were usually drunk. Fridgi-Dinner's target audience was bar and tavern owners, who were forever trying to find something else to feed their patrons besides peanuts but preferred to not have to set up a kitchen or pay someone to cook in it.

Meanwhile, other companies were trying the idea out in smaller markets. In 1949, the Bernstein brothers launched the ingeniously named Frozen Dinners Inc. in Pittsburgh, which sold its horribly, horribly named "One-Eyed Eskimo" dinners exclusively to locals. By 1954, One-Eyed Eskimo frozen meals were sold all over the eastern United States. The frozen meal was on its way up.

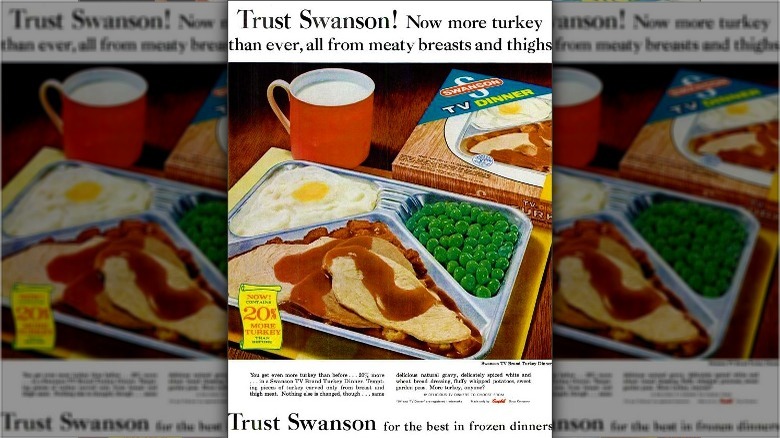

There was the great 1953 turkey surplus

The story of how Swanson claims to have invented the frozen dinner is actually eerily reminiscent of the story of how Maxson himself actually developed it. It all started with a surplus, but in Swanson's case it was a huge, potentially expensive surplus. In the weeks after Thanksgiving in 1952 — you know, when the whole country is sick of the sight of turkey — the company found itself with 260 tons of uneaten Thanksgiving poultry. To buy itself a little time, Swanson loaded all those surplus turkeys onto a refrigerated train, which rather inconveniently did not work as a refrigerator unless it was moving. To keep the turkeys from spoiling, the train had to go on a long back and forth trip while executives tried to figure out how to solve their 260-ton problem.

That's when a Swanson employee hit upon the brilliant and not-totally-unique idea of packaging the turkey up with gravy, cornbread stuffing, sweet potatoes, and peas and selling it as individually portioned frozen meals. Sources are mixed on how exactly Thomas came up with this flash of originality, but nobody thinks it came to him in a dream or anything. He either had tried one of Maxson's Sky Plates on board a Pan Am flight, or he got the idea while visiting a plant that made packaging for frozen meals. Either way, it's clear he seemingly stole the idea, though Swanson always claimed the frozen meal was their own invention.

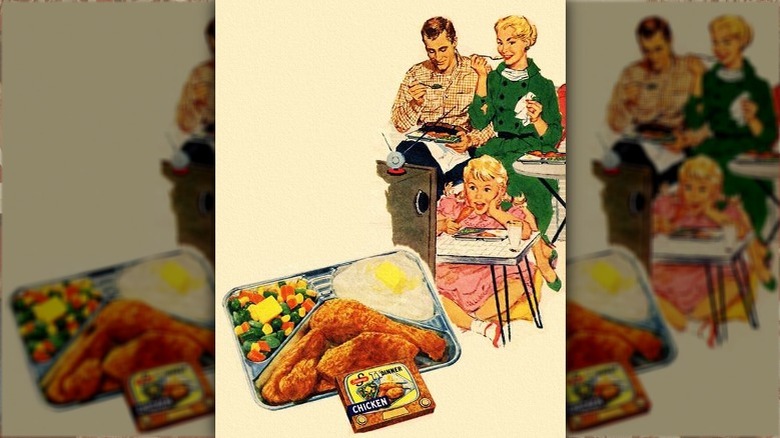

TV dinners appealed to brand new TV owners

Okay, so why the name TV dinner then? Well, coincidentally, Swanson's idea coincided with the invention of the TV tray, which also happened to coincide with the decline of the family meal. You see, 1953 was just after the dawn of the television set, and a lot of families were abandoning boring family dinner conversation in favor of "Dragnet" and "I love Lucy." After all, there was no such thing as a DVR, so if you weren't sitting in front of the tube when your favorite show aired, you'd miss it. This impossible problem necessitated the invention of the TV tray, so mealtime with the spouse and kids would never again have to interfere with important television watching.

The problem with 1950s dining in front of the TV was that someone still had to cook (the wife) and someone had to wash the dishes afterwards (the wife). And then the TV dining experience wasn't as much fun for the wife. So Swanson decided to do its part to nudge American families down the long, sad road of not talking to each other anymore, and it branded its frozen meals TV Dinners, featuring minimal prep and cleanup so everyone can take part. It even designed a cute box shaped like a television screen to make it clear to everyone exactly what you were supposed to be doing while you ate those dinners.

Swanson stamped out the little guys

Before Swanson, the frozen ready-to-eat meal was the domain of the entrepreneur, the brainchild of necessity, the little-guy's chance to rise to the proverbial top of the business ecosystem. Unfortunately for all those up-and-coming entrepreneurs, Swanson was a big name with a lot of money, and money often trumps ingenuity.

Swanson's frozen TV dinners were cleverly packaged, priced at an affordable 98 cents, and available in grocery stores all over the nation. In the first full year of sales, Swanson sold 10 million frozen dinners. The year after that it sold 25 million of them. Where is the Fridgi-Dinner today? It's not in your local tavern or grocery store, that's for sure. Neither are One-Eyed Eskimo dinners, though that's somewhat less of a tragedy.

Swanson wasn't totally without competition, though — Stouffer's and Banquet also wanted a piece of the frozen turkey pot pie. Stouffer's was once an Ohio restaurant chain, but it also sold frozen starters to people in too much of a hurry to cook from scratch or come in for a sit-down meal, and it developed its own line of frozen meals around the same time as Swanson. Banquet, which began its business with frozen meat pies, introduced its own line of frozen dinners in 1954.

The peak of TV dinners: the dessert compartment

If you ate frozen meals as a kid, your memories of the dessert compartment are almost certainly more vivid than your memories of the peas and carrots. It's probably even safe to say that some of us only ate the dessert while sneaking the rest of the meal to the dog, assuming the dog would go anywhere near the peas and carrots.

But the dessert compartment was not always a feature of the TV dinner. In fact, it didn't even make its first appearance until 1960. Early TV dinner dessert options included apple cobbler, cherry pie, or a brownie, all of which seemed to come out of the oven in varying states of being overcooked, undercooked, still frozen in the middle, or tongue-burningly hot. Didn't really matter, though, it was still the first thing you ate before offering the rest of the plate to Fido.

The dessert compartment was introduced after Campbell's Soup Company took over Swanson's frozen meal line, keeping only the name. Campbell's was also responsible for branching out of the dinner sector into the breakfast sector with the 1969 launch of Great Starts.

NFL stars helped sell Hungry-Man

By today's standards, the portion sizes of an Swanson's original TV dinners were but a microcosm of what humans need to survive in modern America. As early as 1973, Campbell's realized that men didn't want to eat like rabbits; they wanted big, high-calorie meals that would keep them satisfied during not just one episode of Gunsmoke, but also during all the episodes of everything that aired before and after Gunsmoke.

The new "Hungry-Man" line of frozen dinners featured larger portions, lots and lots of meat, and had a celebrity-fueled marketing campaign featuring NFL stars "Mean" Joe Greene and Rocky Bleier of the Pittsburgh Steelers who were featured in several commercials for the line. It's unclear just how many calories were in the original Hungry-Man meals, but it's thought that they contained around 4,000 calories, nearly double what even the hungriest man — perhaps even an NFL player — is supposed to eat in an entire day.

Le Menu tried to make TV dinners gourmet

Up until the 1980s, TV dinners were really just about convenience. If you were in a hurry or you were too tired to cook, you popped a TV dinner into the oven and you didn't really worry too much about how ordinary it was, because it was just an easy way to fill your stomach. Then, in the 1980s, the concept of the foodie was born. Suddenly, people cared about food in ways they had never before cared about food. They didn't just want to fill their stomachs, they wanted to fill their stomachs with something extraordinary. Frozen meals? How pedestrian.

Naturally, the frozen food industry saw this as a dire problem, but Campbell's thought they had the answer: Le Menu (because le is French and apparently that means fancy!). With the Le Menu line of frozen TV dinners, instead of eating chicken nuggets or Salisbury steak, you could enjoy pepper steak with long grain rice and "crisp Oriental vegetables," or chicken cordon bleu with glazed baby carrots and rice pilaf. And it worked, too. Consumers returned to the frozen foods aisle, sales got a boost, and the TV dinner lived on.

Kid Cuisine helped give busy parents a break

Adults of the 1990s wanted to eat healthy, but anyone who's ever raised a kid or two understands that most would rather starve to death than eat a piece of broccoli. If you really want your kids to eat enthusiastically, sometimes you have to offer food that is either deep fried or smothered in melted cheese.

This may be why Kid Cuisine was such a hit when it debuted in the 1990. Around this time, single income families were becoming less common, and moms had a lot less time to spend whipping up a wholesome lunchtime meal or even a wholesome dinner. Busy parents needed a fast and efficient way to feed their children, and Kid Cuisine was the answer. The frozen meals featured kid-friendly flavors like chicken nuggets and hamburger pizza in a convenient microwaveable tray. The packages also came with a warning: Don't let your kids cook this unsupervised. But what's a few steam burns in the grand scheme of raising kids who can "cook" their own meals?

Now that helicopter parenting is back in style, it may surprise you to hear that Kid Cuisine did not go out of business. They exist, but with revamped offerings that are aiming to be slightly healthier than their predecessors (which basically just means there's a serving of corn for kids to ignore and toss into the trash after they're done polishing off the brownie).

And then people decided to eat healthy

By the 1990s, people were starting to realize that what you eat has a lot to do with how healthy you are. Doctors already knew that, of course, but regular people were finally acting on the advice medical experts had been giving them for decades. This was the era of the low-fat and fat-free diets, which saw people rejecting frozen chicken nuggets in favor of foods made with fresher, healthier ingredients. Even today around 40% of American consumers think frozen foods aren't nutritious, no matter how many servings of vegetables there are. In 1998, the FDA tried settling this debate when it published research that found no difference between the nutritional value of fresh foods and frozen foods, but that hasn't stopped people from believing otherwise.

It wasn't just a desire to eat healthier foods that fueled the slow rejection of the frozen dinner. It's also not especially cost-effective anymore to eat ready-made frozen meals, so why pay more money for presumably less healthy food? By 2008, frozen dinner sales were in decline and the frozen food aisle started to shrink, which left manufacturers scrambling to find a new strategy.

The sad end of Swanson TV dinners

From its humble origins featuring excess cauliflower and too many turkeys to the frozen food aisles of today, the frozen TV dinner has come a long way. But sadly — or happily, depending on your perspective — Swanson's part in modern, frozen cuisine is but a fraction of what it once was. Today the Hungry-Man line of frozen meals is the only thing left of the original Swanson TV dinners, and the name doesn't even appear on the packaging anymore.

That's partly because the brand has changed hands so many times. In 1998, Campbell's spun off its Swanson TV dinners line into a new company that would eventually become Pinnacle Foods. However, the business struggled for a decade until it was acquired by conglomerate Conagra Brands in 2018. Today, Conagra still owns Hungry-Man, which is still trying to appeal to hungry men (and women!) everywhere, but in a much less calorie-heavy way. Modern Hungry-Man meals typically have less than 1,000 calories, which can still be pretty hefty, but not quite as artery-clogging as the Hungry-Man meals of the past.

Things are looking up though, for now

Billions of lives were turned upside down during the COVID-19 pandemic, but there were a few positive outcomes, especially from certain business perspectives. Namely, the frozen dinner market got a major boost while everyone was in lockdown. Stuck at home, unable to have dinner parties (because dinner parties aren't really that much fun over Zoom), and hard pressed to find staples like potatoes and rice in the picked-over local grocery store, our eating habits changed and consumers started opting for frozen ready-made meals more often. Why waste time in the kitchen when the only people you're feeding are yourself and your Boston terrier?

Thanks to that COVID-fueled boost, today's frozen TV dinner market is worth about $41 billion. Analysts think it may be worth as much as $130 billion by 2029, though it's unclear what experts think will be driving that — let's just hope it's not another lockdown.