The Untold Truth Of Hershey

There's probably no one in America who hasn't had a Hershey product of one kind or another. They're such a staple it's impossible to think of a kitchen (or checkout line) without them. Hershey was founded by Milton Hershey at the turn of the century, and he wasn't always the successful philanthropist we think of today.

The story of Hershey is one that embodies what we think of when we talk about the American dream: overcoming adversity, working hard, building a life and a legacy. The man — and the company — has a fascinating story that involves failed business ventures and bankruptcy, a European inspiration, and even a near-death experience. Today, Hershey is synonymous with chocolate, but it wasn't an easy road by any stretch of the imagination — and it didn't start with chocolate. Along the way, he changed the nation's sweet tooth, built a city, and built lives for thousands of employees and children given a chance by his charitable organizations. Let's talk chocolate.

Chocolates were an afterthought

Today, Hershey is synonymous with chocolate. It wasn't always that way, though — Milton Hershey's first major foray into candy-making was in the world of caramel.

According to the Hershey Community Archives, Hershey failed twice before opening the Lancaster Caramel Company in 1886. Though the third try did end up being the charm, the company came close to completely failing.

Hershey was plagued with bad credit after previous failures, and his caramel company was in serious danger of failing, too. A bank cashier came to the rescue by co-signing the loan himself, giving Hershey the cash he needed for a batch of raw ingredients that would keep the company going. It started to grow, and by 1892 he was buying competitor's facilities. Hershey's caramels were made with the finest imported ingredients, and eventually included products called Paradox, Empire, Icelts, Jim Crack, and Roly Poly. His involvement in caramels was ultimately short-lived but profitable — he sold the caramel business in 1900 for $1 million. In today's money, that's almost $30 million.

Chocolate was only for the rich before Hershey

When Hershey sold his caramel business for a turn-of-the-century fortune, he was only letting part of his candy empire go. In 1893, Hershey had gone to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and attended a demonstration of a German chocolatier. The demo included machinery that made the entire chocolate-making process easier, and Hershey saw an opportunity.

Until then, chocolate was time-consuming to make and expensive to buy — more of a luxury item. Official Hershey history says that changed with Hershey's purchase. He had the machines shipped back to his caramel plant with the intention of making chocolate-covered caramels, but the chocolate was such a hit that his business became all about the milk chocolate. He rethought his business plan, started making "Hershey bars," and changed candy history by making affordable chocolate available to everyone.

There's a strange footnote to Hershey's trip to the 1893 Exposition, as he wasn't the only one inspired by the estimated 27 million people there. The James Beard Foundation says it also launched Cracker Jack, Juicy Fruit, Aunt Jemima, and Cream of Wheat, and it's where Pabst won their Blue Ribbon.

Hershey almost sank with Titanic

Decades after it sank in the waters of the North Atlantic, the Titanic still holds an eerie sort of fascination for us. It's easy to see why: it changed transportation forever, and it changed history, too. There were passengers that could have gone on to have a major impact on the world, had they lived. Milton Hershey was almost one of those passengers.

Hershey Community Archives director Pam Whitenack says (via Penn Live) that Hershey was a confirmed passenger on the Titanic's ill-fated 1912 voyage. He and his wife had been vacationing in Nice, France, for the winter of 1911, and when it came time to head back to the States he booked passage on Titanic. Whitenack says it's not clear what happened to make him change his plans, though it was likely work-related — the matter was so insignificant it wasn't recorded — but Hershey ended up booking passage on the Amerika, and leaving Europe just four days before Titanic. (Catherine stayed behind to continue medical treatments she was receiving overseas.)

From rags to riches

Rags-to-riches stories might seem like they're a dime a dozen, but Hershey's story was shaped by incredible hardship. Born Milton Snavely Hershey on September 13, 1857, Hershey had one younger sister who died when she was 4. His father was prone to what Hershey History calls "get rich schemes", and all of those schemes — which included a trout farm — failed. Attempts to find that one last working scheme meant a lot of moving around, so young Hershey attended seven different schools before ultimately ending his formal education at the fourth grade.

Hershey then embarked on a series of failed ventures. He was dismissed from an apprenticeship as a printer, declared bankruptcy after opening his first candy company, and traveled across the country in a failed attempt to get in on a silver mine. He tried another candy business in New York City, and the doors closed on that one, too.

Hershey's family — who had invested in his failed businesses — largely shunned him. The exception was an aunt, who gave him a loan to buy his first caramel-making equipment. He spent days making candy, nights selling them from a pushcart, and found his calling.

Everyone thought he was nuts

One of Hershey's failed businesses was in New York City, so he'd experienced first-hand just how difficult it was to build something special in the city. So when it came time to build his chocolate empire, he headed out to rural Pennsylvania — in spite of the naysayers. The Milton Hershey School says everyone from business associates to friends told him not to build in the country, but there was a method to his madness.

The plots of land Hershey chose were close to the Berks and Dauphin Turnpike, as well as the Reading and Philadelphia Railroads. There was a massive labor pool of rural families who were ready to work, and it was also close to one of his factory's main ingredients: fresh milk. Even state officials resisted Hershey's plan to incorporate a town, but he persisted. The first streets — Chocolate and Cocoa Avenues — were laid, and the first houses went up (via Hershey History), and Hershey finally got a Post Office in 1906.

The friendly company town

Hershey's early struggles meant that he understood what it was like to wonder where your next meal was coming from, and when it came time to provide for his workers, he went to the extreme.

He started by designing and building Hershey, Pennsylvania as not just a company town, but as a place the workers in his factory would be proud to raise their families. The town's official history says it grew up in the earliest days of the chocolate factories, and included not only nice houses and affordable transportation, but a park, amusement park, ballroom, swimming pool, and much of the construction happened during the Great Depression. Hershey put as many builders to work as he could, building stadiums, arenas, theaters, and community centers as a part of what he called the Great Building Campaign.

The MS Hershey Foundation followed, and when Hershey and his wife, Catherine, realized they would never have children, they established the Hershey Industrial School for orphans. It's the Milton Hershey School today, and it's helped thousands of children.

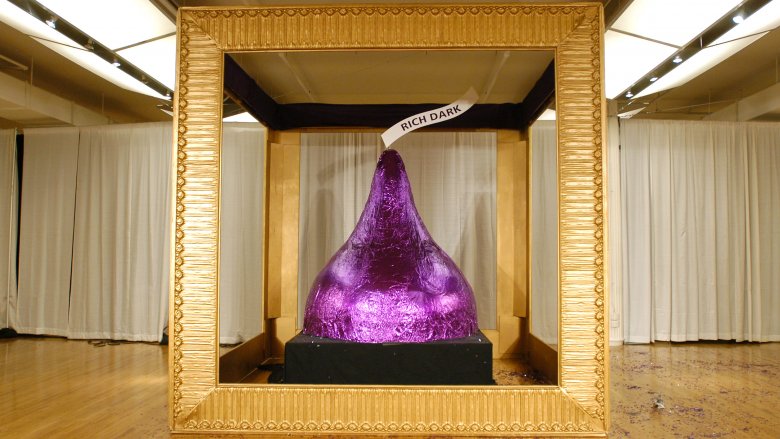

The Kiss is a copycat

Hershey's Kisses are almost unthinkably popular. They're so popular their Hershey, Pennsylvania location turns out 70 million Kisses a day, and that's a ton of chocolate. Literally! Their popularity only helped contribute to the internet's surprise when someone pointed out (via Business Insider) that there's a Kiss hidden right in the logo, and it shocked the world that no one noticed that until 2017. Even more surprising is the fact the Kiss is a copycat.

According to Time, Hershey released the Kiss in 1907 — 13 years after another Pennsylvania chocolatier named Henry Oscar Wilbur introduced the Wilbur Bud.

The chocolates had the same shape, but while the Bud was created using individual molds, the Kiss was mass-produced with a machine that plopped them onto a conveyor belt. Hershey also came up with the innovation that sealed the Kiss's popularity: individual wrappers, making them into a product people could take anywhere. (And, until 1921, each Kiss was wrapped by hand.) The Bud didn't go down without a fight, though, and candy historian Samira Kawash says HO Wilbur tried — unsuccessfully — to sue the copycat company in 1909. They failed, and the world kept the Kiss.

The Kiss's urban legend

The popular story is that the Kiss was named for the sound the machine makes as it drops each one on the conveyor belt, but Time says that's just an urban legend. The truth is actually a lot stranger.

Hershey only trademarked the name in 2000, and that's because it's actually a generic name for a piece of candy wrapped with a little twisty bit. The term dates back to at least the 1820s, and throughout the 19th century it was actually defined in dictionaries as simply referring to "A small piece of confectionary." Since it was such a generic term, Hershey wasn't allowed to trademark it — it would be like Papa John's trying to trademark the term "pizza." Candy historian Samira Kawash says that into the early 20th century, there were all kinds of kisses on the market. You could pick up some molasses kisses, violet or blue bell kisses, lucky kisses, or even honey corn kisses.

Fast forward decades, and it wasn't until 2000 that Hershey convinced the courts the "Kiss" had become so firmly associated with them it was a part of the brand, and they won their trademark.

Mr. Goodbar's accidental history

Mr. Goodbar is one of Hershey's most iconic products, and even critics have to admit it has an excellent name. It's friendly, it's catchy, it's easy to remember... and it was a complete accident.

According to the Hershey Community Archives and a bit of oral history from Hershey chemist Samuel Hinkle, the company started thinking about putting peanuts in their product in the 1920s. It took a surprising amount of experimentation and led to Hershey's use of Spanish peanuts over Virginia peanuts, and when it came time to come up with a name for the bar of chocolate and fried-in-fat peanuts, it was a complete accident. Hinkle says someone remarked, "That's a good bar," and Hershey — who was going a bit deaf at the time — misheard it as "Mr. Goodbar." The name stuck through decades of some fascinating marketing.

During the Depression, Mr. Goodbar was advertised as a great way to get a filling, high-nutrition lunch at a reasonable price, and that idea of a nutritional chocolate bar stuck with it through the 1950s and 1960s. Post-war, Mr. Goodbar was marketed as the original energy bar. Not exactly the way you'd see a chocolate bar marketed today, but hey, different times!

They played a big part in WWII

For years, the Allied army was faced with not just training and arming men to send to Europe and the Pacific, they needed to feed them, too. That process started in 1937, when the army approached Hershey and asked them to design a heat-resistant, high-calorie, high-nutrition chocolate bar soldiers could carry through extreme temperatures as a source of portable, compact soldier-fuel. The Hershey Archives says it was Sam Hinkle who developed the bar to not only resist the heat of the Pacific theater, but contain some extra vitamins and nutrients that would help protect soldiers against tropical illness.

By 1939, Hershey was cranking out 100,000 Field Ration D bars a day, a number that skyrocketed to 24 million a week in 1945. Over the course of the war, Hershey supplied around 3 billion of the bars to soldiers worldwide, and it made such a difference in the war effort Hershey was given a military medal — and every employee also got recognized for their contributions. Later, that same chocolate bar would be used by another government agency: NASA. Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar made it to the moon, in the pockets of Apollo 15 astronauts.

Reese's Peanut Butter Cups were invented by a Hershey castoff

Peanut butter and chocolate are the soulmates of the candy world, and they've been together since at least 1907. Atlas Obscura says during those early days, they were a weird mix of health food (the peanut butter) and candy (the chocolate). They were a novelty for decades, until Harry Burnett Reese was laid off from his job at Hershey, and decided he was going to start his own candy company.

Reese was following in his mother's footsteps, too, when he started out making her chocolate-covered raisins and almonds. After working for Hershey, he asked for their blessing — and permission — to start his own company. They gave it, as long as he bought his chocolate from them.

Reese agreed, and in 1928 a chance conversation with a candy store owner gave him the nudge he needed. With help from a 50-pound can of peanut butter, Reese developed his peanut butter cups. After struggling through the Depression and getting a helping hand from Hershey to make it through World War II rationing, the company took off. It eventually merged with Hershey in 1963, and secured the fate of the peanut butter cups.

The syrup started off very differently

Hershey's syrup is the stuff of chocolate milk and ice cream sundaes, but not all their chocolate syrup was made the same. Chemist Sam Hinkle was behind this product, too, and according to the Hershey Archives it took an insane amount of work for researchers to figure out how to turn chocolate into a stable, liquid product that could be canned and shipped across the country.

Once they had the basics, Hershey developed a single-strength and a double-strength product — and it was only available to their commercial customers. The double is what we're more familiar with, and it was first sold as an ice cream topping. The single was sold to places with soda fountains, and was used to make some chocolatey carbonated beverages.

By 1928, Hershey's salesmen were getting requests for a non-commercial version, and Hershey's obliged. There are a few other landmark dates in the history of Hershey's syrup: they started making their own metal cans in 1956, and replaced them with plastic bottles in 1979.

Why Swoops were swept away

Remember Swoops? Hershey introduced them in 2003, and as unthinkable as it seems, they were a chocolatey treat that failed in a pretty epic way and disappeared three years later.

According to Fast Company, Hershey stumbled on this one for a few reasons. The shape of Swoops made us think of Pringles, but there was no crunchy, potato-chip center (or even a sweet candy center). That shape was meant to encourage mindless snacking, but since there weren't many Swoops in a container, they were hugely unsatisfying. There was also a weird thing that happened when you started looking at the nutritional information of Swoops, too — you'd find out you were better off buying a plain Hershey's candy bar. Add in the fact you could buy about three chocolate bars for the price of a pack of Swoops, and all that meant they didn't survive past the stage where they were seen as a new novelty.

Child labor may be involved

In 2015, The Daily Beast reported on a pretty shocking lawsuit that involved not just Hershey's, but Mars and Nestle as well. The suit claimed they weren't being honest about the fact their supply chain relied on the use of child labor to harvest the cocoa. West Africa was targeted as the location of the worst of the human rights violations, as that's where about two-thirds of the world's chocolate comes from. The suit claimed that anyone who purchased any of Big Chocolate's products was being duped into supporting slave labor, and that's a pretty serious accusation.

The issue first came to light in 2000, with a documentary that filmed the kids who were harvesting the cocoa, not being paid, and being beaten for trying to escape. Hershey — and their competitors — promised to join a global movement to end the use of child labor, after Hershey came out and said the documentary was the first they'd heard of what was going on. The issue is far from settled. In fact, Confectionary News reported on more lawsuits filed in February 2018, first against Nestle then against both Mars and Hershey's.

They have a top-secret science lab

Anyone who goes to Hershey's Chocolate World can play around with making their own chocolate bar, and that's pretty cool. They see just what happens along every step of the way in the process, but there's another lab not far away that's so secret most employees don't even have access.

It's a nondescript looking building that houses all Hershey's trade secrets, so it's not surprising that Penn Live says security is approaching Fort Knox levels. It's full of winding hallways, security doors, and safety windows, and they also say Hershey goes through a strangely complex process that doesn't involve just chocolate and flavors. They're also studying things like the impact of colors, sales statistics, and consumer psychology. They're also doing some top-secret science to help them target international markets, too, changing up American staples and adapting them to global tastes. Go to Canada and you'll find Hershey's chocolate is creamier, and in Brazil, it's got a smoky taste. That all comes courtesy of their secret Pennsylvania labs.