Grocery Stores That Sadly Disappeared

Running a grocery store is tough. The business has frighteningly thin profit margins — only 2.2% net profit in 2017, and competition from home delivery services and losses from shoplifting are both making the field more competitive and harder to work in (via Forbes and Forbes). In fact, according to Marketplace, one of the reasons you see so many private-label brands is that they allow for better profits. What looks like a busy store to customers might be on the chain's chopping block because the chain wants to streamline operations, or because the chain is being bought out by another company. Even the big names have been closing stores lately, making some wonder whether these grocery store chains will close.

Chances are very good that at least one market you used to shop at has closed, and the 20th century was rife with once-popular names disappearing. Some closed as a result of mergers and buyouts. Others disappeared due to anti-trust complaints. Some simply couldn't keep up with the competition or made no effort to really show customers why they should shop at these stores. That's not to mention the ones that got taken down by mismanagement and hefty legal fees. Still, these stores were fixtures in people's lives for years, and despite all the problems that may have led to their closure, the memories of a favorite brand or logo still linger. Here's a look at some of those grocery stores that have sadly disappeared.

Alpha Beta

Alpha Beta was a trailblazing California-based chain that created the concepts of both the self-service grocery store and the supermarket. Brothers Albert and Hugh Gerrard of Pomona, California, started with a butcher shop in 1900 and eventually expanded into the grocery business in 1914. It was in these shops in 1915, per the Daily Bulletin, that the brothers let customers get their own groceries instead of having clerks retrieve them. Customers initially had no idea where things were, though, so the brothers decided to stack products in alphabetical order. That worked so well that they renamed their market Alpha Beta in 1919 (via the Los Angeles Times). In 1932, the brothers opened two markets that were much larger than their original stores; according to the Los Angeles Times, these were really the first supermarkets as we would recognize them.

In 1961, the chain merged with American Stores to increase its financial strength. American Stores was a public company, and that meant it was subject to leveraged buyouts. That happened in 1979 when Skaggs took over American (retaining the American name). In 1988, American bought another grocery chain but had to sell the Alpha Beta stores in 1991 to investment firm Yucaipa Companies to resolve an anti-trust lawsuit. Yucaipa later bought the Ralph's chain in 1994 and renamed the remaining Alpha Beta locations as Ralph's, according to LAist.

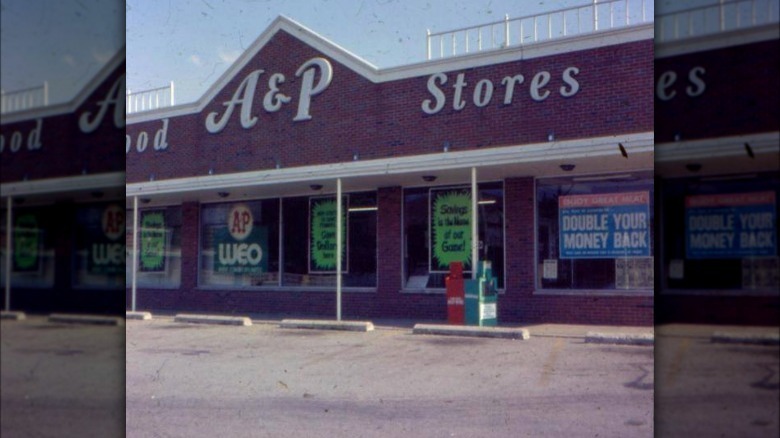

A&P

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. was a stalwart of the East Coast and Midwest grocery scenes for decades. The company started as a tea company just before the Civil War in 1859, per Groceteria.com, and later branched out to sell other products. Expanded inventory and good pricing led to customer loyalty, which allowed A&P to move into several states and become a major success. The company was able to expand from the East Coast to the Midwest and eventually even to California. At its peak, A&P had over 15,000 stores, according to Reuters.

The 1950s were times of growth for the company, but many smaller stores in the chain were being closed in favor of the larger supermarket format. The company had also lost track of a strategy that initially made it successful. According to Groceteria.com, A&P originally would sign only short-term leases for its stores because the company wanted to be able to move to where people were moving. By the 1950s, the company was no longer that nimble. In the 1960s and 1970s, the situation got worse as the California stores were closed and the company started opening new store formats that fell flat. Sell-offs and store closures continued, culminating in two rounds of bankruptcy in 2010 and 2015 after the company faced adverse changes in terms from suppliers, according to USA Today. The financial losses were too great, and the last A&P closed in 2015 (per Classic New York History).

AppleTree Market (Texas)

AppleTree Market (one of a few unrelated but similarly named chains across the country) was a short-lived but popular chain in central and southeast Texas that began as part of a major division sell-off by Safeway. In the 1980s, Safeway was heavily in debt and facing a hostile takeover, according to Houston Historic Retail. To avoid this, Safeway agreed to let another company buy it out in 1986, but as a result, Safeway had to start selling divisions, and fast. Several stores in Texas were sold and rebranded as AppleTree in 1989, but despite the stores' popularity with customers (via Houston Press), over the next few years, the stores dealt with some corporate neglect as renovation plans fell through.

Houston Historic Retail notes that AppleTree had been negotiating with grocery unions since 1990 while the company was suffering financially. By 1992, AppleTree was desperately trying to cut costs as it declared bankruptcy, including asking workers to accept pay cuts and loss of health insurance. This led the unions to threaten a strike. A court intervened and, per the Texas State Historical Association, canceled the union contracts; the TSHA put the demise of AppleTree squarely on the strike that ensued, though the Houston Chronicle pointed out that fewer than 10% of the chain's employees joined the picketers. Local competition also increased, and in 1993, AppleTree began selling stores. A few locations lingered on into the 2000s, with the last AppleTree closing in 2009 in Bryan.

Dominick's Finer Foods

Dominick's Finer Foods was a Chicago stalwart from 1918 to 2013. Named after its founder, Dominick DiMatteo, it sold products that, according to Dom Capital Group, were hand-picked by DiMatteo each morning at greengrocers and other sellers. The chain initially didn't grow that quickly, having only seven stores by the early 1960s. In 1968, per the Encyclopedia of Chicago, the chain was bought out by Fisher Foods, although the company kept the Dominick's name. However, in 1981, Dominick DiMatteo Jr. bought the company back from Fisher.

That's when Dominick's really took off. The company added video rental, prepared foods, and other divisions, and kept expanding stores. Things looked generally great until DiMatteo Jr. died in 1993, at which point the family decided to sell the company. Yucaipa Companies bought the chain in 1995, and in 1997, Safeway bought the markets. The trouble for Dominick's started just a few years later.

First, Safeway made Dominick's run more like its other stores, replacing favorite store brands with Safeway brands and ending special orders (per Zippia). Waves of firings and resignations struck management, customers rebelled, union negotiations stalled, and Dominick's got sued by Michael Jordan (via NBC Chicago). Then, in 2011, several customers reported finding expired products on store shelves, with one blogger finding 435 products, some dating back to 2008 (via CBS News). By 2013, Safeway decided to sell its remaining Dominick's stores to different companies.

Double 8 Foods

Indianapolis-based Double 8 Foods provided a necessary service in parts of the city that didn't have much in the way of grocery stores. In fact, when the chain closed in 2015, the Indianapolis Star interviewed several customers who were worried about where they could shop next. The Star noted that Indianapolis had more food deserts than other U.S. cities. But the family-run chain had to close because the chain was losing money, and the owners wanted to sell but couldn't find buyers (via WTHR).

The chain started out as Seven Eleven Supermarkets in 1957. Zoltan Weisz opened one market, named after its hours, and slowly expanded to six stores by 1971. Something the company was noted for was that in 1959, it hired an African American manager, the first in Indiana (via Double 8 Foods). After Weisz died and the store was handed to his grand-niece and her husband, Elana and Isaiah Kuperstein, the name was changed to Double 8; Isaiah Kuperstein told the Urban Indy blog in 2010 that the name referred to the day the store opened, August 8, as well as the Kupersteins' anniversary. They continued to manage the store as before, but by 2015, they didn't have the revenues to continue (via WTTV). No one would buy the chain, so they closed all of the stores suddenly in July of that year.

Fresh & Easy

Fresh & Easy was the U.S. branch of U.K. grocery company Tesco, which first announced in 2006 that it planned to open stores in the U.S. (per the BBC), and initially, no one knew what to make of it. An analysis by eNumerys noted that no one was sure what type of competition the company would face. Analysts were divided, with some calling the move risky and others pointing to Tesco's huge success in the U.K. as an indicator that it knew what it was doing. It turns out the stores had issues almost immediately.

Tesco was aggressive, opening Fresh & Easy stores in Southern California, Phoenix, and Las Vegas in 2007, according to CSP magazine. Its gimmick, in addition to selling groceries, was something called cold-chain delivery for prepackaged meals, which Tesco had used successfully in the U.K. However, the meals didn't click with Americans. Customers thought the quality wasn't that great, and CSP magazine noted that the size of the U.S. made the delivery system untenable.

Fresh & Easy failed to distinguish itself from other brands, and in 2013, the chain declared bankruptcy. Tesco sold the stores to Yucaipa Companies, but their intervention wasn't enough; Fresh & Easy filed for bankruptcy again in 2015. The stores closed in the same year. The Los Angeles Times reported that employees said Yucaipa didn't do enough marketing to attract customers after making changes and never defined why people should shop there instead of in other markets.

Henry's (aka Henry's Farmers Market and Henry's Marketplace)

Back in 1943, Henry and Jessie Boney started a fruit stand in La Mesa, just east of San Diego. That stand grew into five stands and then full stores, at which point the Boneys sold the stores so they could run their new convenience store chain (via San Diego Union-Tribune). But the Boneys returned to the grocery business in the 1970s when sons Steve, Stan, and Scott opened Windmill Farms, which later became Boney's. In 1997, the brothers renamed the chain Henry's Marketplace. However, two years later, the Boney family sold Henry's to Wild Oats Market, something that Shon Boney (Stan's son) told the San Diego Union-Tribune they regretted doing.

After the sale, Stan and Shon couldn't open another market in California due to a state-specific non-compete agreement, so they went to Arizona and started the Sprouts chain, quickly growing that into a multistate operation (via San Diego Union-Tribune and Press Enterprise). In 2007, Whole Foods bought Wild Oats and sold the Henry's division to Smart & Final. The Boneys struck a deal with Apollo Management, owners of Smart & Final, in which Sprouts, a Texas chain named Sun Harvest, and Henry's would merge; Apollo would be the majority owner, but the Boney family would manage the chain's operations. All the Henry's Marketplaces and Sun Harvests were renamed as Sprouts; Shon Boney told the Orange County Register that they used the Sprouts name because that chain had more locations.

Hinky Dinky

The next time you get cash back at the grocery store, take a moment to thank Hinky Dinky, a Nebraska-based chain of grocery stores. The chain started back in 1925 in Omaha as a local competitor to the Piggly Wiggly chain (via North Omaha History). Hinky Dinky was innovative in several ways, according to Omaha Magazine. It was big on automation, with automated doors and checkouts, and kept meat and other frozen goods in refrigerator and freezer cases that the customer could access. Hinky Dinky was the first chain in the region to use wheeled grocery carts. And in January 1974, the chain became the first to have terminals at the checkout stand that allowed customers of First Federal Savings & Loan Association of Lincoln to withdraw cash (via Time).

Hinky Dinky was sold in 1972 to Cullum Cos., which also owned the Tom Thumb markets in Texas (via Supermarket News). Cullum used Hinky Dinky's profits to support Tom Thumb but neglected Hinky Dinky in return. A union strike in 1984 plus competition from non-union stores led Cullum to sell Hinky Dinky (via Supermarket News). Interestingly, Omaha Magazine says the last Hinky Dinky stores closed in 1985, but the chain actually lived on for a few more years, with Nash Finch buying the company's stock in 2000 and rebranding the stores (via Company-Histories.com).

Hughes

Hughes was something of an outlier in the Southern California grocery scene because of its founder's extreme caution and refusal to join any mergers. In the mid-1950s, Thriftimart franchise owner Joseph Hughes opened the first Hughes Market in Granada Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles (via LAist). Hughes was very cautious about making changes or expanding in-store services. Growing the chain was a slow process because Hughes did not want to take on debt to open more stores, which was an unusual attitude at the time (via Encyclopedia.com). One of Hughes' successful innovations was introducing fresh fish in the stores, something that other Southern California chains weren't yet doing.

After Joseph died in 1982, his son Roger, who had been managing another Hughes, continued the no-debt expansion of the chain but got more assertive in finding opportunities to open new Hughes locations. This strategy was a success, and Hughes quickly grew into a billion-dollar company (via Encyclopedia.com). Roger Hughes was originally averse to the idea of taking the company public, but by 1997, he changed his mind and merged the chain with Quality Food Centers; Hughes markets remained in operation after being sold to Yucaipa Companies in 1998 but were rebranded as Ralph's in 1999 (via LAist and Los Angeles Times). Unfortunately, the Ralph's merger put some Hughes jobs and facilities at risk of closure, something that Roger Hughes had tried to avoid during the initial merger with Quality Food Centers.

Jitney Jungle

Jitney Jungle was a Mississippi-based chain that started in 1919 as a typical credit-and-delivery store where customers would send in orders that clerks would fill and deliver. According to the Mississippi Encyclopedia, the founders decided to change the store to a self-service model. The savings from having to pay fewer employees went toward price discounts, and the chain developed a reputation for low-cost groceries. As the market expanded, the company was careful to follow its customers as they moved out into the suburbs. One other notable feature at a location in Jackson was a women's bathroom. That doesn't seem so strange now, but back then it was a clear signal that it was catering to its female customers. By the 1950s, Jitney Jungles were marketed toward women as social destinations where they could meet up with their friends. According to Encyclopedia.com, the chain even offered chairs for children who would wait for their mothers in the store. The chain also expanded into a few other states in the South.

The company remained privately owned for most of its existence, but in 1996, a New York investment firm offered the financial resources the owners needed to expand (via Supermarket News). When the merger was complete, the chain expanded rapidly, and so did expenses. You can guess what happened next — unfortunately, the expenses grew too large, and Jitney Jungle had to file for bankruptcy. The last stores were sold off in 2000 and 2001 (via The New York Times).

National Tea

National Tea was a Chicago company that began in 1899 and quickly grew into one of the largest grocery chains in the region. It was hit hard by the Great Depression, but according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, even that devastating time couldn't kick National Tea out of the top 10 list of biggest American grocery chains. National Tea was known partly for bringing products from farms to its stores, allowing farmers to sell items that were normally too perishable to sit in a distributor's warehouse (via Telegraph-Herald and Times-Journal). In the 1950s, National Tea was bought by George Weston Ltd, a Canadian retailer (later called Loblaw), and renamed National Supermarkets (via Encyclopedia.com). In 1995, Schnucks Markets bought the National chain only to sell many of the stores to avoid anti-trust violations (via the Federal Trade Commission).

This is where National Tea's story becomes rather surprising. Some of those stores sold by Schnucks were purchased by an investment manager named James R. Gibson. He ran a firm that set up lifetime payments for people who had gotten large insurance payouts by buying Treasury bonds. However, it was revealed that Gibson diverted millions to other costs, including personal property improvements and purchasing the National Supermarket chain. He was sentenced to over 40 years in prison, and the National Supermarket name faded away (via Supermarket News, Supermarket News, and NBC News).

Tidyman's

Tidyman's, based in Spokane, was formed in 1965. The stores were named after Jim Tidyman, a mechanic in Montana who started a warehouse-type grocery store even though he didn't know how to run one, according to the Puget Sound Business Journal. He had to learn a lot, fast, but he did so easily. Tidyman's expanded to Washington and Idaho, and Tidyman moved the headquarters to eastern Washington. Tidyman's was a non-union store, and the employees rejected efforts to unionize the store. At that point, one union called for a boycott, but Tidyman courted more conservative customers who weren't fans of the union. In 1984, Tidyman decided to sell the shares of the store to the employees. Tidyman's became employee-owned in 1986, and the chain continued to expand.

In 1992, Tidyman's was fined by the Department of Labor for using child labor; the case was one of the largest in the Pacific Northwest (via Spokesman-Review). Then, in 1999, the chain was ordered to pay an eye-opening $6.2 million in a gender discrimination lawsuit brought by two female employees who claimed they were not considered for promotions. The amount was so great that it put Tidyman's future in jeopardy (via Spokesman-Review). The chain's management didn't invest a lot in the stores, and by the mid-2000s, Tidyman's locations were outdated and suffering a drop in staff morale, according to the Spokane Journal of Business. In 2006, Tidyman's sold off its stores to pay its debts (via Moscow-Pullman Daily News).