Cecilia Chiang: The Woman Who Brought Chinese Food To America

In nearly every corner of the United States, you can find good Chinese food. As noted by Time Magazine, in 2016, the number of Chinese restaurants in America easily outnumbered fast food behemoths like Taco Bell, KFC, Pizza Hut, and McDonald's restaurants combined. Chinese restaurants reflect a larger immigration of Chinese people to the States in the late 19th century, following the Gold Rush on the West Coast – especially merchants from Southern China who flocked to the region in hopes of either getting rich or feeding those who were trying to (via Time Magazine).

Arguably, it was 100 years later that modern Chinese food entered the scene, and that was thanks to one woman: Cecilia Chiang. A retrospective from NPR credits the restaurateur with redefining how Americans perceive Chinese cuisine. The article notes that as Chiang entered the scene, Chinese food was practically synonymous with dishes like chop suey, which is Chinese-American in origin (via The Smithsonian Magazine). Chiang worked to make and sell a rich variety of Chinese dishes like those she had grown up with. Among American luminaries like Alice Waters and Julia Child, Cecilia Chiang is someone who deserves to be a household name.

Chiang was born into a life of luxury

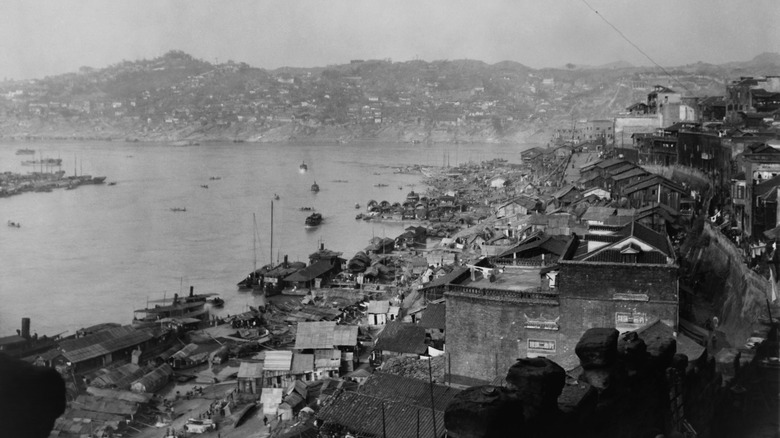

Cecilia Chiang was born in the city of Wuxi in Southern China. Her early life was extremely charmed; she was born into an incredibly wealthy and, by all accounts, loving family (via The New York Times and Washington Post). According to the Times, her mother, Sun Shueh Yun Hui, was the daughter of a prominent flour mill and textile family and was accustomed to running the finances of her birth family. Meanwhile, her father, Sun Long Guang, was a railway engineer who was successful enough to retire by age 50. Despite their more technical leanings, Chiang observed in an interview with Eater, that they were very much artistic in nature. The restaurateur recounts that her family home was filled with music, fine arts, and the like. She also makes a point to mention that it was very important to her father that his children, all 12 of them – including all his daughters – be educated. While it was uncommon for women of this class to pursue higher education in the early 20th century, her family considered it necessary.

Chiang is described by The Washington Post as growing up in the extreme luxury of a 52-room mansion, where all her needs were catered to by a waitstaff. While nowadays her name is synonymous with cuisine, as a child she was not even permitted to set foot in the kitchen. Her life, however, would change drastically by 1942.

The Sino-Japanese War forced Chiang to flee her home

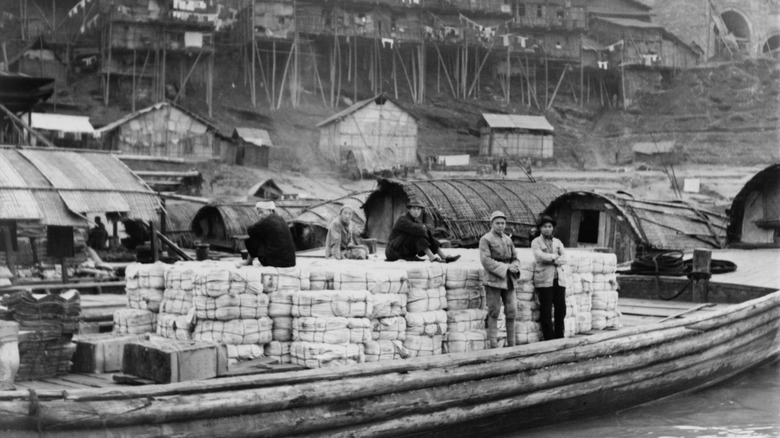

The charmed life for Chiang came to an abrupt halt in the '30s, as Japanese forces came to invade and then occupy China. By 1939, as observed by The New York Times, that life had become so dangerous that the once privileged family turned to drastic measures to survive. The Marin Independent Journal clarifies that when the Chiang family home was invaded and ransacked by Japanese soldiers, it became clear that life could not go on in the way it had before. On one cold January morning in 1942, Cecilia's mother covered two of her daughters in a carriage to get them past city lines, beginning their long escape to the South of China.

Chiang, who was 20 and a recent grad at the time, noted the absolute horrors surrounding her escape. As she recalls in her interview with Eater, she and one older sister walked over 1,000 miles by foot over six months. As The Washington Post notes, the girls subsisted on as little as flour and water, were robbed, and, according to Cecilia herself, had to walk at night and rest during the day to avoid aerial attacks. According to The Washington Post, Chiang's father chose to not bind his daughters' feet, which was a customary practice for privileged families at the time. This decision, undoubtedly, aided in both Chiang sisters making it to safety in the South.

Chiang worked as a spy and later fled China completely

By the war's end in 1945, Chiang stayed settled in Southern China, where she met her husband, businessman Chiang Lang. Soon she became a mother to two children, May and Philip. But family-building wasn't all that she was up to. In post-war and pre-communist China, Chiang became a spy for America's Office of Strategic Services, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. This was presumably to monitor and report on details surrounding communist political movements in and around the social circle; details remain vague even to this day.

Nonetheless, by the time the Communist Revolution came into full swing, Chiang, her spouse, and their daughter boarded the last flight out of Shanghai in 1949, according to The Marin Independent Journal. While some of Chiang's family members survived the Second Sino-Japanese War, many were lost directly and indirectly to many separate tragedies as the revolution took hold (via The Marin Independent Journal). The Chiang family settled into Tokyo, and Cecilia's life in China as she knew it was gone.

The now legendary chef made it into American gastronomy by a twist of fate

Cecilia Chiang wasn't a chef by trade in any sense of the word, but ultimately, restaurants provided a way for Chiang to stay connected to her culture as she assumed status as an ex-patriot. The US Dandelion notes that there was a certain functionality to Chiang's first restaurant opening in Tokyo: She simply missed Chinese food and wanted to curate a space where it could be enjoyed. Forbidden City was, as described by Chiang's interview with Eater, nothing short of a massive restaurant that could seat 350 people.

It was fate that brought Chiang to the States. One of her surviving sisters had immigrated to San Francisco and was newly widowed. In 1960, Chiang arrived in California by ship, seeking to console her sister in a time of need (via US Dandelion). Staying on her couch, as described by the publication, the two sisters found themselves traveling through neighborhoods in Chinatown to find good spots to eat.

Bored by the seemingly endless chop suey and tea, it seemed like perfect timing that Chiang would run into friends from Tokyo who were looking to open a restaurant in Chinatown. As the best English speaker in the group, Chiang negotiated for a restaurant space nearby and even cut a check for $10,000. As her friends got cold feet and bowed out, Cecilia found herself the sole owner of her first independent restaurant (via US Dandelion).

The Mandarin was Chiang's first and most famous restaurant

While some might throw in the towel, Cecilia Chiang was not willing to cut her losses on the restaurant. The deposit had been paid, and she was going to try to do as much with the 60-seat space as she could, and in any case, hadn't Chinese-American food been disappointing her? In fact, it seemed like Chiang's disappointment in what she had tasted in California fueled her vision for the restaurant, lovingly and meaningfully named The Mandarin.

As described by The Washington Post, Chiang had a few rules going into her new restaurant and most of them were what was not to do. The owner wanted absolutely no chop suey on the menu, which was practically unheard of considering just how popular it was at the time. So popular in fact, that The Smithsonian Magazine reported it as popular as "hot dogs and apple pie."

Nonetheless, Chiang wanted a restaurant that leaned away from stereotypes: No lanterns and dragons, and no gold (via The Washington Post). In 1961, Chiang personally opened The Mandarin with a specific design to provide a traditional Chinese fine-dining experience that those born in the States may very well have never experienced before. While she was still on her way to becoming the grand dame of Chinese food (a title later given to her by The Washington Post), she had certainly arrived.

Chiang wanted to offer real Chinese food that wasn't readily available

Sure as The Mandarin would not lean into visual Chinese stereotypes, the menu was designed with just as much intention to provide an authentic experience for guests. While Cecilia Chiang wasn't a chef, she did have a strong appreciation for fine dining, according to The Berkeley Library. This was coupled with an amazing sense of taste that even stunned the likes of other American luminaries like Alice Waters (via Eater). Though Cecilia may not have been behind the stove or preparing the meal herself, she was both designing and tasting all that was being served, according to both sources. That being said, Chiang herself credits her own success to her sharpened palate and taste. After all, it's one thing to be able to make good food, and it's another to be able to discern what exactly has made it so good. It's interesting to note that The Mandarin was run by Chiang's taste both in food and aesthetics.

Chiang wanted patrons to have a taste of the hallmarks of Chinese cuisine, which meant not offering up the typical menu, but focusing instead on Mandarin and Sichuan flavors. Ever one for the grandiose, Chiang noted that her original menu had around 300 items, including beloved chicken and duck dishes along with the more obscure sea urchin and the now controversial, yet traditional, shark fin.

She faced many challenges as a business owner

Though Chiang had a strong vision of what the restaurant and menu would look like, the restaurant's opening was not without its struggles. After all, serving up dishes that people were unfamiliar with didn't encourage a strong following at the beginning. It wasn't just the food that was off the beaten path; quite literally, The Mandarin was physically located just outside of Chinatown and, as noted by Eater, was without any parking or easy way to reach it by walking. The cards were stacked against Chiang, but she reported that there were other factors that worsened the chances of her restaurant surviving. In the aforementioned interview, Chiang said that as a female business owner, she often faced discrimination in terms of money lending. Very rarely was anyone willing to bet on a woman in business, especially if she were running it herself. There simply were no major female restaurateurs at the time.

Additionally, the majority of San Francisco's Chinatown was, as described by Google Arts & Culture, a sub-group from Southern Mainland China who spoke Cantonese. Chiang, who spoke Mandarin and was raised in Wuxi, recalled how impossible it was to build beneficial inroads in the area. She described herself as being treated as a "foreigner," since she didn't speak the same language. As the Berkeley Library reported, for the first six months of The Mandarin's initial opening, it was basically deserted.

It took a review to put the now-beloved restaurant on the map

So much of Chiang's life seemed to be dependent on timing, and perhaps it was timing that was responsible for The Mandarin not only surviving but thriving. Chiang was taken by surprise one day when a white guest approached her speaking fluent Mandarin, according to Eater. He praised her dishes as being the first authentic and good Chinese cuisine that he had since leaving the country. Auspiciously, it was the owner of a once very famous restaurant in China who now, having tasted Chiang's menu, was determined to help her out (via Eater). He advised that the restaurant needed to be put on the map, and he had an idea of how to do so.

Two days later the restaurateur returned to The Mandarin with legendary San Francisco journalist Herb Caen as his guest. Caen was assured that he would finally taste real Chinese food as he dug into Chiang's dishes (via Eater). Not only did Caen begin frequenting The Mandarin, but he began writing effusive reviews. As San Francisco's Chinatown website observes, Caen's first rave review seemed to be the push the restaurant needed. Both sources note that as soon as the review was published, the phone began ringing off the hook with people clamoring to taste exactly what Caen had described.

The restaurant soon became revered by foodies and celebrities alike

Herb Caen's review highlighted the extraordinary food that was already being plated and served within The Mandarin. It wasn't long before the restaurant was able to move to the iconic Ghirardelli Square, working with a multi-million budget, according to The New York Times. As the magazine describes, the new restaurant could seat well over 300 people while still maintaining a "temple-like" atmosphere that provided a large yet welcoming space to sample all that Chiang could conceptualize. It was no longer a secret just how good the food was, and as The Mandarin began to expand and open new locations, it also came to accommodate larger-than-life figures. The Mandarin in Beverly Hills became a favorite of John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and Elton John when they were in town, according to the Times and the San Francisco Chronicle. Paul Newman was also known to have an open tab with the restaurant, according to the magazine. As the latter source noted, at its height, The Mandarin had seven hostesses on staff to be able to manage the flow of hungry patrons who were ready to know what all the fuss was about.

Cecilia Chiang was a huge fixture of the restaurant as well

Arguably, the prospect of meeting Cecilia Chiang was just as big a part of experiencing The Mandarin as the food or its well-curated setting. The Washington Post described her as having an "elegant" presence that no doubt contributed to the all-around allure of the restaurant. It wasn't just that Chiang played a heavy hand in the decisions surrounding the eatery, even seeking out vintage items that spoke to a vision of her girlhood in China and a bygone era that had disappeared all too quickly (via Library of Berkeley). Chiang exuded a refined demeanor and was hard to miss as she made her rounds on the restaurant floor. In a 2020 retrospective from Coupar Consulting after the passing of Chiang at 100 years old, the site reports that she was known for wearing glamorous gowns and jewels even while on the clock.

In an article from SF Gate, one previous employee recounted that Chiang was renowned for knowing people by name and adding a graceful yet warm presence to the room. He mentioned that the waitstaff often hoped that Chiang would visit one of their tables as she was making rounds, as the tip attached to the bill would surely go up. Likewise, according to the site, Chiang was known for treating her staff well and compensating them in a way that was unusual for the times.

The Mandarin is considered to this day to be revolutionary

Cecilia Chiang brought regional Chinese cuisine not only into the restaurant scene, but into the mainstream. Chinese food had long been synonymous both with Cantonese cuisine specifically and viewed as a cheap eat for laborers (via The University of California and Time). Cecilia Chiang worked intentionally to introduce and honor the diversity of Chinese cuisine. As noted by NPR, Chiang drew inspiration from diverse regions, but history was the biggest inspiration for the now legendary cuisinière. The article alludes to the idea that the biggest influence on Chiang's palate was dishes sourced from a time that had long since passed. NPR touches upon a documentary that focuses on Chiang, "Soul of a Banquet," where one food magazine editor notes "memory" played a large role in Cecilia's palate. The documentary posits that when eating Chiang's menu, guests have the chance to taste Chinese cuisine that isn't all too common anymore. In a sense, somewhat romantically, when sitting down at The Mandarin, one is invited to taste what colored Chiang's childhood so beautifully.

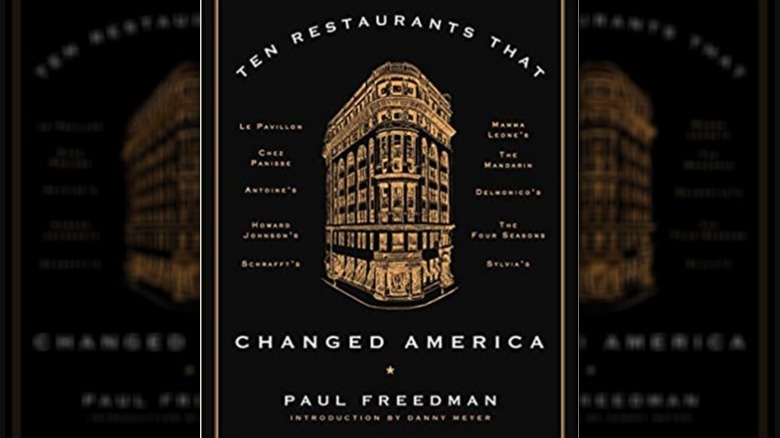

There are many different aspects to Chiang's success in the food world. It remains inarguable just how large her influence has been. In 2016, historian Paul Freedman published a book featuring Ten Restaurants that Changed America. Among them, of course, was Chiang's. Freedman argued that not only did Chiang widen the country's understanding of Chinese cuisine, but also of Chinese people.

Chiang went on to teach other legendary American chefs

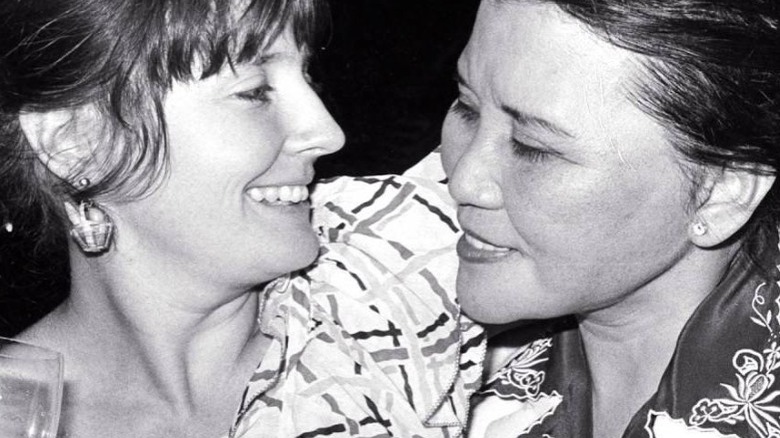

Chiang's influence wasn't just limited to those with a table reservation; many prominent chefs turned towards her for an introduction to the cuisine as well. While Chiang is often referred to as the Julia Child or Alice Waters of Chinese food, these comparisons seem a bit unfair given she is credited with having mentored both chefs in Chinese cooking (via PBS and Forward). Really, Chiang should be considered a name of her own.

Nonetheless, it's possibly Alice Waters, the other gastronomical luminary of California, that Chiang had the strongest ties to, which cumulated into a 50-year friendship according to Apartamento Magazine. After The Mandarin had taken off, Chiang began hosting a cooking course at the restaurant. It was through this class, and the insistence of a food writer, that Waters first met Chiang. The queen of seasonality, Waters gave a nod to Chiang's rotating and fresh ingredients that made for incredibly harmonious meals. When reflecting on the chef's influence, Waters observes that it's Chiang's curation and presentation that most influenced her personally. She praised Chiang's use of different cooking techniques, textures, and varying complexities of the meals. She also remarked that Chiang's meals would always begin boldly and conclude with a quiet end, leaving the diner with a fond memory of each fine dining experience.

Chiang's son went on to co-found P.F. Chang's

Interestingly, Chiang's influence was passed down a generation. In the 1970s, when Cecilia Chiang took an extended trip to China, Chiang's son Philip began to manage The Mandarin. As his mother took a step back, Philip eventually became the owner of the iconic restaurant, per The LA Times.

By the '90s, Philip opened his own restaurant, a smaller offset of The Mandarin called The Mandarette. Ever inventive, the Times described the Mandarette as a bit more laid-back in nature. It was intended to be a coffee shop with simple dishes. It was here that Philip Chiang came into contact with Arizona-based restaurateur Paul Fleming, and by 1993 they partnered to open none other than P.F. Chang's.

As noted by the P.F. Chang's company site, The Mandarette had been Fleming's favorite restaurant as the menu featured delicious meals that often featured only three or so ingredients. So great was the influence of The Mandarin on the opening of P.F. Chang's that the restaurant still credits the restaurant to this day (via P.F. Chang's). While these accomplishments are surely a credit to Philip himself, it is still impressive to see the groundwork that Cecilia Chiang had laid to bring two generations of creative, and delicious, cooking.