Michael Twitty's New Book Koshersoul Brings Two Culinary Worlds Together - Exclusive Interview

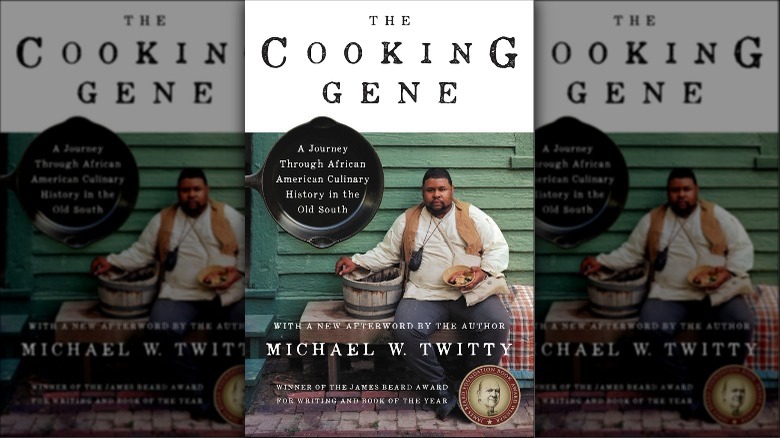

Culinary historian Michael Twitty made a name for himself tackling untold truths and underrepresented groups through the lens of food. Twitty first made waves by founding "Southern Discomfort Tour," which gave a hands-on experience to show the influence of Black cooking on Southern cuisine, while fighting racism. His first book, "The Cooking Gene," continued this exploration, along with providing personal insight into Twitty's life and heritage. "The Cooking Gene" earned Twitty a James Beard award.

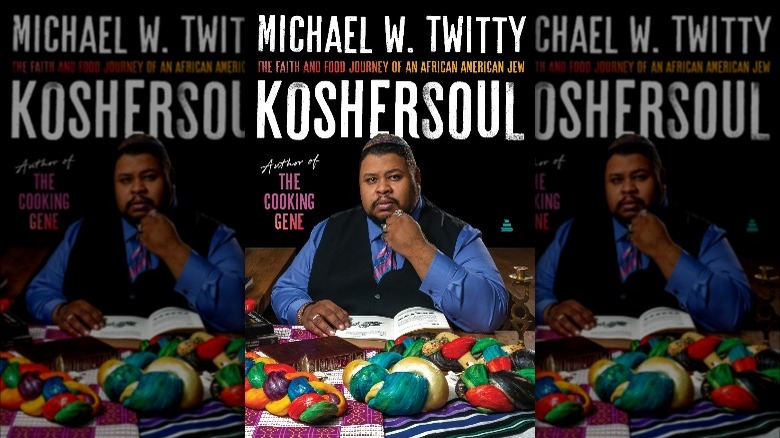

With the release of his new book "Koshersoul," Twitty is tackling another part of his identity: that of being a Black Jewish man. The category may seem novel to some, but as Twitty makes clear in his book, they are not a group to be tokenized. He once again weaves a seamless web between personal experience, history, and the community at large. We sat down with Twitty in an exclusive interview to talk to him about "Koshersoul."

Writing about food

How did you first get interested in food, and writing about food?

It goes back to the whole family kitchen thing, but it was enhanced by the fact that I would spend virtually every Saturday afternoon watching — cartoons were in the morning, but cooking shows were afternoon, into the night. At that point, there was no Food Network, no cooking channel. Having those food programs on made me feel grown. I spent a lot of time thinking about the terms, the terminology. My mother, of blessed memory, had me copy down an entire list of culinary terms and memorize them.

By-and-by, every now and then, I'm asked, "What are the presents for holiday?" I asked for one of those cookbooks from TV, and that's how I learned how to cook, between that, and my mother, and my grandmother, and my father.

Who were the biggest food influences?

Martin Yan, Justin Wilson, Graham Kerr, Natalie Dupree, [and] Joan Nathan. Nathalie Dupree had a show called "New Southern Cooking."

For me in particular, that show was really extraordinary because it illuminated that part of my heritage. A lot of things that she talked about, my grandmother could have referred to. I would often watch the show without her and then run to ask her to verify the things that I had seen and heard on the show. Many years later, I got to befriend Natalie and stay in her house. It was really weird. I stayed with her a couple times ... Everything comes full circle.

Family influences

Within your family, who else were influences?

My mother was my absolute most important food teacher, bar none. My mom was the smartest human being I think I'll ever know in this life. She was extraordinary. The thing that made her unique wasn't only [that] she pick[ed] up the tradition from my grandmother, but she could do anything. If she was interested in something and wanted to learn something, she could do anything. She was the one person I would watch some of the cooking programs with, her and my father. I didn't grow up tightly woven with my parents. This was also a bonding thing [for] my father and I, in particular.

My father would take me down to the farmer's markets, especially the Black ones. The Black ones were not the pretty ones in the park. They were beneath bridges and other stuff. [We had] conversations of meeting these watermelon farmers from North Carolina or people bringing up tomatoes or okra from South Carolina, apples from Virginia, and crabs from Maryland. Daddy would take me and explain things to me. My father grew up half in the city, half in the country. [I remember him] teaching me about how to grow things, gardening.

Between my parents [and] my grandparents, [I learned] different things about not just food, but their own history. I can't tell you how every day of my life, I take for granted the fact that I had living grandparents who essentially were from the 1910s [through] 1920. [They] could tell me about a world that now it's becoming extinct, especially Black life in the Jim Crow South during the '10s, '20s, and '30s.

That caught on as part of your food culture — not just segregation, but the fact that the community was self-reliant. The community fed itself, even when the world was falling apart during the Depression. Both of my grandmothers adamantly said something that apart from each other was extraordinary. They said that during the Depression, the white folks begged at our back door. That was because these were country people. They knew they were going to plant that next crop. They knew they were going to grow that next thing. Food was the one thing that they weren't going to run out of.

My grandfather had lived all over the world as part of his job, and my mom got to see England, and East Africa. He was a negotiator for railway unions in the former British Empire. Decolonization was a big part of our story as well. I'm grateful for this unusual childhood and rearing that I had that was so intertwined with food. My grandmother learned how to make what we might consider to be a curry of some sort from East Africa, from her Indian and Sri Lankan neighbors. That wasn't something she would've experienced in America. I grew up eating things from all over the world and didn't really know where the world began and where we ended.

Writing the book

What made you want to write this book, Kosher Soul?

I wanted to tell a story. Right now, we're dealing with the aftermath of several very strange Kanye interviews. How do you beat that back? How do you tell people, "Please stop mythologizing us. Please stop making us exotic. Please stop over-exaggerating our minority of minority status as Jews of color, Jews of African descent." How do you tell people you're everyday ordinary people? You tell them about your food. You tell them about how you break bread with your family. You tell them about the traditions that you're trying to create and pass on.

Knowing that there weren't any books about Black Jews, and how we eat, how those food traditions can develop, and how they can be passed on — I wanted to create that record. It's always about creating a blueprint or a record or a first effort with me. I'm not satisfied with letting someone else tell the story or letting these things go. It's not about entertainment either. A lot of people go into food, and they want to learn about food for the entertainment aspect.

It's, "Can I duplicate a recipe?" They're all about the recipe. I'm all about the people, and their lives, and their stories, and what the influence of their lives have had on the food that we prepare, and how that food helps define who we are.

The meaning behind Koshersoul

What do you define as kosher soul?

I've kept it open ended, because I didn't want to be the brand rep. Sometimes, that happens. I've been making the joke recently that we learned our lesson from the preppy handbook, and from the grunge dictionary, and the hipster manual. These things are like pseudo, they're made up. They're not real. They're done to sell the idea of a culture to executives who will buy these books and start talking some weird grunge language.

No one ever said, "Kurt Cobain never really said more than five words at a time, and I can understand all of them." It's not like you spoke a different language. I didn't want to write "Kosher Soul," the expose, right? I wanted to write "Kosher Soul," an exploration of how different Jews of African descent make food, how food makes them.

Both terms are very quasi-ethnic. Kosher can double as Jewish, but it can also be a universal term, originating in the idea that "kosher" in Hebrew means to be richly fit, according to the Torah. Soul can be both. Yes, the essence of soul can be the essence of Black culture, Africanness, African Americanness, Negros, too. It could also be the soul food, and soul culture of other people as well.

It's [now] in vogue to say Korean soul food or Greek soul food ...I get that. That's totally okay and applicable. At the same time, it's still a term that originated in the African American community to describe a certain feeling and essence that is otherwise like the umami of culture. What is it? You'll know it when you get there.

Those two things were from my original Twitter handle, koshersoul. I wanted that to be the name for this broad swath of activity. No one's really documented this before. I wanted to say all these people do this differently, but to all these people, cooking, entertainment, hospitality, the Mitzvah of rejoicing in the holidays, and the Sabbath, all of those things are interwoven in all of their lives.

It's the dietary laws, but it's also the importance of the food expressed. The fact that we have this heritage — if you look at it across the board, all these people have talked about having these origins in majority Black areas of the South, the Caribbean, etc. That's real, and on top of these religious connections, what bonds them together? No matter what they may look like, what color they may be, that's all there, yet retaining their unique stories.

Overlap with soul and Judaism

What is the natural overlap between soul food and Jewish cooking?

People are traveling and living in the same places, and they're going through some of the same pressures: exile, enslavement, war, trade. They will mix and meet and exchange culture, especially when they push the margins. I say in the book multiple times that the original sin of the West, other than the generic human sense of misogyny, classism, and other phobias, is definitely anti-Blackness and antisemitism.

Antisemitism is the older of the two. The fact that they both began to merge together and create a template for how the rest of the world's non-white people will be dealt with for the next 500 years — if you actually read that into the history, it's pretty astounding. It's pretty devastating.

In the quest for colonial and imperial power and engagement, India, the Americas, the Pacific Islands, and many other parts of the world were dealt with. The people of Australia were dealt with in the same ways that Europeans had dealt with, in terms of antisemitism and anti-Blackness, in terms of their demands of compliance, and relinquishing of heritage, and genocide, and enslavement, and exile, and also second class citizenship.

It's a reminder that a lot of our food history and food stories aren't the happiest, but it's also a reminder about the resilience of human beings and the hope they bring to surviving and overcoming. I talk about this as being a Black, gay, Jewish, Southern writer. I come from four groups of people who know how to survive. They know how to overcome, and they know how to do it with a joke, even if horrible things have happened to them. We know how to do it with humor.

This book is very much a hybrid. It's a little food memoir, a little cultural story book, and it also has recipes. Why did you choose this format?

It's easier for me. It's a braiding, it's a weaving, like the challah on the cover. Some people like me will read a cookbook like you read a novel, but other people can care less about the person's life or their stories or what they have to offer.

The recipes to me are source documents. It's also a way of just telling people there's a lot more to this than what you see. I have a very ample bibliography in the back where I go into, "You want to learn more? Here's where you go." If someone were to do that work and do their own personal work, they'd be led in a great direction. That's not going to work if I give them a bunch of recipes, and I say, "That's it."

I wanted to make sure they understood that when we use the phrase "Black Lives Matter," it doesn't just refer to people on the pavement. It's about people's everyday life, Black joy, and Black overcoming of trauma. That's having food, celebrating with each other, and honoring our holidays and holy days represent to us.

Coming together

Who do you hope will come to this book?

Americans, giving that swath of humanity, and saying, "Wow, look at all these people vibing on the same note." It's about me saying, "There is something so powerful about us talking to each other." Conversation is not surrender. It's the beginning of an opportunity for mutual self respect and understanding of the boundaries that we must keep and the open doors we must have. In such a divisive climate, there have to be some cultural offerings that give people a roadmap to finding a common piece. I'm not a kumbaya guy. I don't believe if we just eat together, everything is cool. No, it has to be sincere, with meaning, and effort.

How do you showcase "culinary justice" in your book?

A big part of American Jewish contributions to our culture, and our intellectual climate, has been the principles of social justice, which come out of our Torah tradition of repairing the world, making the world a better place, and doing good deeds. At the same time, African American cultural-political life has been undergirded by this idea of changing the world for the better, overcoming oppression, and using moral persuasion to change the world.

Culinary justice is rooted in protecting the culinary resources of the people who are marginalized and oppressed, and amplifying them for their benefit. It undergirds everything that I do here, because I want people to know that the gardens that I've given suggestions about are there so we remember and empower those communities, which have been often exiled, taken off the land to go back to the land to grow our food culture and food supply from the ground up.

It's about getting the narratives down so that no one can make up false narratives later about where things come from. In food history and the culinary world, there's so much made up food lore. That's because nobody ever talked to the people, especially the women. The women who innovated, and created these things often got left out. Dudes can make up any story they want. You notice that most food origin stories almost never contain women. I wonder why?

The Earl of Sandwich didn't make that sandwich. Thomas Jefferson did not bring that damn steak and fries to the table. Come on now. He never cooked a damn thing. He had an army of enslaved people starting with not just Fanny, and Edith, of late, but James Hemings, the first great American chef, who was a Black man. Oftentimes, people who are pushed to the margins and oppressed are left out of the stories of our food.

It's almost never a woman. This can't be true because we know how much in history men would often take credit for what women innovated and invented. The fact that we're acknowledging all those things, and trying to push out a new narrative, means this book is very much vested in culinary justice.

Vulnerability

Was it difficult to be so vulnerable in your book?

Absolutely. Vulnerability is a key ingredient in my writing, because you have to ask the question, "What makes you unique as a writer? What is your voice?" I can be very confessional. I can be like, "I don't really want to talk about this." Part of that comes from the fact that I talked about my grandparents earlier.

Sometimes it wasn't easy to talk to them about their past because a lot of people from their era, you didn't talk about the bad stuff, and you didn't talk about these traumas that afflicted Black life. You left those to your peers and your spouse, but not your children and grandchildren. Part of me also wanted to break that trend of not being able to talk about these things. I respect the new generation's urge to say, "We don't really want to be triggered or be traumatized or re-traumatized".

I respect that. Some of us need to stay in the room and testify because we have to. We have to be able to create a record so that we can correct these mistakes for the present and the future.

That's why I'm vulnerable. There's certain things that I really wanted to talk about that I didn't end up talking about because I was like, "I can't do it. This is not the right time." It's hard. It could be very difficult to sit down at that computer and talk about things like when I was teaching Hebrew school. I had a lot of days when I had a lot of little miracles happen. I had other days when I did feel the pressure of being the only Black person and person of color in a building.

I remember one day, there were these two women walking in the hall who worked in the office of the synagogue, and they were calling Obama a terrorist and joking about it, and I was in the library. They couldn't see me. I felt like there was a huge divide between the aspirations that I felt at that time for having both my parents and my grandfather around [while there were others] glomming onto this early right-wing nonsense that has now infected more people.

This wasn't the same event. This is the dream of 400 years of being in this country and suffering and struggling. What happens when you have nobody to talk to about that? What happens when you've been in these places and taught over a thousand kids? There were a lot of vulnerabilities and a lot of issues and a lot of sore points that could be very hard to get through a day of writing. It's also made me feel a lot more confident the next time I do this to expand and challenge myself and tell new stories, because I didn't get to tackle them here.

The future

Are there plans for a third book?

Absolutely. It's going to be about the queer presence in the kitchen. I wanted people to understand that every part of me goes in the kitchen, and I address each part of that in each book. I'm trying to decide what that's going to look like. A friend of mine does a beautiful podcast, and I need to figure out a way to collaborate with him because I wouldn't think it's fair.

We both have this interest. He has been interviewing me and tackling this interest for quite some time. I want to find a way to include him, because he is so unsung, and he's so talented and so creative, and it'd be best if I found a way to collaborate with him on this third project. It's going to be about the queer presence in the American kitchen.

What is one ingredient you can't live without in the kitchen?

Scallions. That's lifeblood. Scallions, lemons, onions, and garlic, period. [I would] extend that to preserved lemon. I have a million spices. It's crazy. It's pretty bizarre. I guess it's hedging my bets. God won't take me as long as I got to use these spices up.

Who's one chef you'd love to have cook dinner for you?

Seeing that I actually got to go to Noma...Martin Yan. I loved watching him growing up. He's mellowing out these days, but I always thought that he made it look so easy, and so effortless, and put so much soul into his food.

"Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew" is available now.

This interview has been edited for clarity.